Scott Spear's 1969 Kenworth has been in the trucking game as long as Spear has himself.Unless otherwise noted, all photos courtesy of Scott Spear

Scott Spear's 1969 Kenworth has been in the trucking game as long as Spear has himself.Unless otherwise noted, all photos courtesy of Scott Spear

Scott Spear's trucking and transportation career began in 1969, the same year Kenworth built the W900A he's dutifully restoring in the suburbs of Dallas, and in that fateful period where America became the world power we know it as today.

From being one of the engines behind the U.S.' dominance in the Space Race, to celebrating the Statue of Liberty's facelift in the 1980s, Spear has seen some of the country's pivotal moments from the driver's seat. He's helped navigate some of its biggest environmental crises as an environmental engineer back when this country didn't take a driver's knowledge of things for granted.

Spear, a native of Panorama City, California, started driving at just 15 years old on his family farm and eventually hauled heavy equipment to build dams in central California, before even graduating high school.

By the age of 19, he was hauling cross-country for a local small fleet, an impossibility today. In fact, much of Spear's life story wouldn't be possible today, but through his 50-plus years as an operator and in other roles in trucking, he's helped expand on the scope of possibility in this country.

The on-ramp to a long career

"Loading it on trucks took two weeks ... It only took 30 minutes to blow it all up." --Scott Spear, on his 1986 haul of fireworks to NYC for the Statue of Liberty facelift's unveiling

"I’ve been in pretty much every niche there is with the exception of cars and cattle," said Spear. "I did frozen food and produce then I got into hauling for Stayco Corporation doing hydromulching."

You know that green stuff they spray on the side of the road to help grass grow and tamp down erosion? That's hydromulching, and Spear pulled the tankers and chemicals that made a lot of that a common sight.

It was a love of trucks from an early age that propelled him to such a long, prosperous career. Spear's uncle had driven trucks, and he'd developed an eye for them. Before he had even turned 21, Spear was eyeing the Freightliner cabovers of a local fleet he "kept bugging" to let him drive.

One of Bert E. Jessup's cabover Freightliners that Spear pined over in his earlier days.

One of Bert E. Jessup's cabover Freightliners that Spear pined over in his earlier days.

That was Bert E. Jessup, one of the Jessup brothers of Gilroy, California, with "big beautiful trucks with 330-inch wheelbases and 45-foot trailers," Spear recalls. "I really wanted to drive for this guy, but I could only drive a 10-speed.

"I finally went by the yard on a Friday after bugging the hell out of him and he finally got fed up and said OK." Jessup's "idea," Spear later learned, was to teach the young gun a humiliating lesson by losing him in Los Angeles and having a more experienced driver come pick him up. He'd never have to deal with Spear's nagging again.

"He said, 'Follow me to San Diego and let's go pick up some potted plants"" to haul into L.A, said Spear. "That was in a 1942 conventional Kenworth with a 220 Cummins motor and a twin stick," not the beautiful then-modern cabover Spear had in mind, he said.

After a quick tutorial on the twin manual, which Spear said was "a blast" to drive, they took off headed south. "Like I said, he was convinced he was going to lose me in L.A. We got separated, I'm not sure how, and he was convinced that I was lost and couldn’t get the truck going."

But the opposite happened.

"I beat him into the dock," he said. "I was down there before he was." Jessup's girlfriend walked up and told Spear "you've got a driving job for the rest of your life," and explained how their plot to lose him in traffic had, happily, backfired.

"I worked for him for several years until I got married, he wouldn’t even give me time off for the honeymoon," said Spear. "He paid extremely well, but ran you ragged, hard hard hard."

[Related: Why a college administrator quit her job and took up trucking]

Another shot of one of Jessup's then "state of the art" Freightliners.

Another shot of one of Jessup's then "state of the art" Freightliners.

According to Spear, that "extremely" good pay was something less than seven cents a mile at that time in the early 1970s, before deregulation. That comes to just over 50 cents, adjusted for inflation.

Cryo to pyro: Hazmat expertise yields new opportunity

By then, Spear's success in trucking had started to make an impression with his buddies. A friend of his, after a beach trip in Spear's Freightliner, decided to start a trucking business hauling cryogenics around the West Coast and invited Spear to drive for them. At this time, the U.S. was pulling ahead in the Space Race against the Soviets, cementing its technological and economic superiority with each new launch and mission.

"They had three brand-new Peterbilts with 425 Cats in them and nice, big sleepers," said Spear. "We all drove team across the 11 western U.S. states hauling cryogenics like liquid nitrogen, hydrogen, you name it. If it had compressed gasses we'd haul them." Specifically, Spear recalls hauling to Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which literally made the rocket engines that sent men to the moon.

The fleet of Peterbilts and one Kenworth that Spear's friends bought to start Damian Transport, their cryogenics hauling business, during the Space Race.Scott Spear

The fleet of Peterbilts and one Kenworth that Spear's friends bought to start Damian Transport, their cryogenics hauling business, during the Space Race.Scott Spear

After that, Spear got in with a company hauling hazmat, a move that would launch a major chapter in his career. "We hauled everything from spent cyanide to vacuum equipment," he said, "spent acid and spent solvents that we'd dispose at different landfills."

"Don't go into business with your friends." --Scott Spear's advice for owner-ops following a 1980s business failure that fit that description

As a "weekend, part-time gig," he worked for Atlas Enterprises hauling hazmat and fireworks. After moving to Texas around 1980, he got licensed to perform firework shows and carved out a profitable niche for himself hauling fireworks and shooting them off at events around the nation.

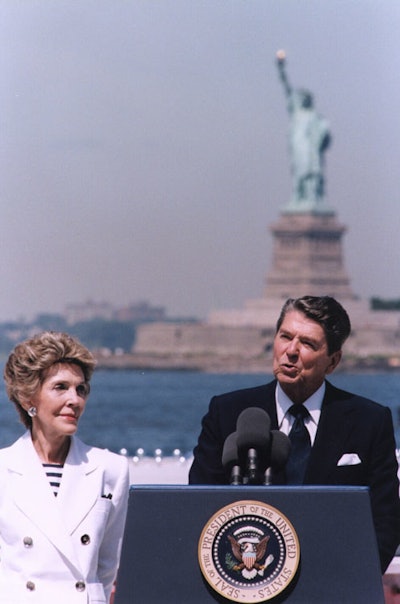

"I was the only one that had a hazmat certificate at Atlas, and they did firework shows all over the U.S., including the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty in 1986 after she was redone," Spear said. "That show consisted of half a million in pyrotechnics alone."

It took two months to put the show together, he added, "with all the choreography and putting all the music and getting it set up to be played on radio and TV. Loading it on trucks took two weeks to get it ready to go," then two days' driving, another couple days unloading and setting up on barges.

"It only took 30 minutes to blow it all up," he said.

President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan on Governors Island on July 4, 1986, just hours before Spear's big fireworks show.Reagan Presidential Library

President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan on Governors Island on July 4, 1986, just hours before Spear's big fireworks show.Reagan Presidential Library

Next, Spear started a vacuum truck business with a friend, and worked there throughout most of the 1980s before leaving on bad terms. "Don't go into business with your friends," he cautioned. During that time, the 80s had become the 90s and Spear moved to Flower Mound, a suburb outside of Dallas, and started looking for work, eventually finding it at Trinity Industries.

"Trinity Industries was one of the biggest rail car manufacturers in the world," he said. "They made highway safety guardrails, bridge girders, red iron. Everything we did was called BMOs -- big metal objects -- anything from automotive to all the red iron for Times Square in New York City."

Spear said he hauled everything from cryogenics to over dimensional 120,000-gallon water tanks for Trinity, but when he was sitting in orientation, his résumé raised some eyebrows at the top of the company.

"The GM of Transportation asked me in orientation, 'Why drive a truck with a résumé like that,'" he said. "He explained that Mr. Jon Sanford was looking for someone that had my experience with environmental health and safety and hauling hazardous waste."

Spear's career hauling hazmat predated much of the Environmental Protection Agency's sleuthing on where hazmat had been buried, so the agency wisely got in touch with Spear back in 1976, and he spent almost two years helping them figure out where the bodies were buried, so to speak. "I'd go out and start identifying these facilities. We were pre-regulatory and companies were dumping [hazmat] in the ground," he said of his correspondence with the EPA, which at that time was more of a correspondence than a job.

Spear had "a lot of knowledge in where these places were," and was able to help track down some truly dangerous sites, he said. Both at Trinity and with his work with the EPA, Spear managed to get his knowledge and tradecraft as a professional driver acknowledged by fleet and government brass.

The road to restoration of a classic

All too often, in today's data-driven world, fleets and regulators discount or overlook an operator's accrued, hard-won experience, insisting on the wisdom in hard and fast, arbitrary-seeming hours rules, or second-guessing a seasoned hauler's knowledge of his own territory with insistence on a piece of software's route plan .

Scott Spear, pictured on the left, at his lifelong friend's auto shop restoring the W900A.

Scott Spear, pictured on the left, at his lifelong friend's auto shop restoring the W900A.

[Related: From wildcatting to deregulation, a 'Brief History of Trucking in America' Over the Road]

He went on to a long career at Trinity, where he eventually became an environmental health and safety manager, and then Vice President of Transportation for the whole company, spending about 10 years in and around Europe, Mexico, Brazil, and wherever else his experienced eye was needed. He retired in 2014, but his eye landed on an ad for a 1969 Kenworth W900A in the American Truck Historical Society's magazine.

A year of correspondence between Spear and the owner passed before he finally lined up the money and time to haul out to see it in California.

"They were so nice, they held the truck for me," Spear said of the previous owner. "The market was flooded out in California with emissions laws pulling trucks off the road, putting a big influx of trucks on the market."

The previous owners, California farmers getting on in years, "picked me up at the local airport, walked out and gave me the keys. I got in, turned the key, fired right off, no issues whatsoever." Spear would spend two nights on the farm checking everything for the long haul home to Texas.

Now the Kenworth sports antique plates, pictured here before much of the restoration.

Now the Kenworth sports antique plates, pictured here before much of the restoration.

"I fixed a few wires and changed the belts, and drove to Texas with not a single problem," he said.

The Kenworth has since traded its commercial plates for antique plates, as shown, joining Spear in a kind of semi-retirement that doubles as a love letter to trucking. Now Spear spends most of his time restoring the rig to its former glory.

"Over the last couple years I've been redoing upholstery and interior" elements, he said. "I polished all of the chrome and it's really turning out to be a real nice truck." He plans a black and red leather interior with live edge wood panels and an epoxy "river" as the floorboards, calling on his decades as a hobbyist in leather and woodworking.

"It’s got a remanufactured small-cam Cummins with the 13-speed, and it's cut down from a three-axle to a two," he said. It "used to haul sand and gravel for local operations," and was cut down when they were forced to take it off the road.

Before and after shots of the rig in Spear's yard in Texas, with the after taking place on a rare icy day. There's a joke in here somewhere about how "that old Kenworth will shine when Texas freezes over."

Before and after shots of the rig in Spear's yard in Texas, with the after taking place on a rare icy day. There's a joke in here somewhere about how "that old Kenworth will shine when Texas freezes over."

The truck originally had a twin-stick manual transmission in it, recalling his earlier days hauling for Jessup, and he hopes to find another to replace the current 13-speed set-up.

Now, as President of the ATHS' Lone Star Chapter, Spear hopes you'll see him at truck shows around Texas and the country as he tries to restart the ATHS Dallas show, previously discontinued after sponsors dropped them.

For a full listing of the ATHS' events and calendar, and the chance to see and hear about trucks and stories like Spear's in person, follow this link.

[Related: What Wreaths Across America means to trucking, and all of us]

from Overdrive https://ift.tt/aDL0xzi

Sourced by Quik DMV - CADMV fleet registration services. Renew your registration online in only 10 minutes. No DMV visits, no lines, no phone mazes, and no appointments needed. Visit Quik, Click, Pay & Print your registration from home or any local print shop.

0 comments:

Post a Comment